ON August 12 1982, 29 years ago, boxing lost one of its finest fighters; Mexico’s Salvador Sanchez. The reigning WBC featherweight champion was just 23-years-old and at the pinnacle of a dazzling career; only 22 days previously he had made a successful defence against an unknown fighter from Africa named Azumah Nelson.

ON August 12 1982, 29 years ago, boxing lost one of its finest fighters; Mexico’s Salvador Sanchez. The reigning WBC featherweight champion was just 23-years-old and at the pinnacle of a dazzling career; only 22 days previously he had made a successful defence against an unknown fighter from Africa named Azumah Nelson.

Salvador Sanchez was born on January 26 1959 in the Mexican city of Santiago Tianguistenco. He was also raised in the city, famous for its bull-fighting and richly-stocked markets.

The Early Years

The young Salvador at first took a liking to wrestling before a friend introduced him to a boxing gym. The skinny young kid fell in love with the sport and boxed for the rest of his life. Salvador was desperate to turn professional so never had much of an amateur career, rumoured to consist of just four bouts. However, the young Mexican impressed an interested onlooker one day while sparring in the gym. Veteran trainer Augustin Palacios was so impressed with the novices’ natural speed and skills he agreed to manage and train Salvador there-and-then. Despite his parents concerns, Sanchez turned pro’ soon after.

In May 1975, at the age of 16, the young Mexican made his professional debut, knocking out Al Gardeno in three rounds. The fight was held in Mexico, where Sanchez would have all of his first 21 fights.

Within two years Sanchez was an impressive 18-0 (17) and improving with every contest, before the future great would suffer his first (and only) loss in a bout for the vacant Mexican title; Antonio Becerra edging the 18-year-old Salvador on a split decision. Some thought Sanchez had done enough in a closely-contested fight where neither fighter gained a clear advantage.

After two more wins in Mexico, Salvador fought outside his native country for the first time, being held to a ten-round draw by fellow Mexican Juan Escobar in Los Angeles. Escobar had lost two of his previous three fights by stoppage but came pumped up and very nearly won. The Mexican southpaw battled the 20-1 prospect all the way, even scoring a knock-down in round five; it would be the only time Sanchez would hit the canvas in 46 fights. The judges’ scores read 94-94, 95-95 and a 97-93 for Escobar.

The Mexican prospect was very upset after the draw (and previous loss) and decided to rearrange his management team and hire a new coach; Enrique Huerta who worked hard on developing his new fighter to box and move more, rather than just slugging and standing flat-footed.

Prospect To Champion

Sanchez was kept busy and won his next 13 fights, scoring ten knock-outs. This winning streak included a five-round stoppage of Puerto Rican champion Felix Trinidad Sr, father of the future welterweight superstar of the same name.

Now a contender and world-rated, Sanchez was pitted against world champion Danny “Little Red” Lopez for the WBC featherweight title. The formidable champion had been champion for four years and was making the ninth defence of his title at the Veteran’s Memorial Coliseum in Phoenix, Arizona.

Lopez was as hard-as-nails, heavy-handed with an exciting style. Never in a bad fight, the grizzled champion was a solid 42-3 (39) and the firm favourite against the little-known Mexican, who had just turned 21-years-old.

Sanchez however, was to be unknown no more. Light on his feet, keeping his hands high and peppering the champion with quick jabs and sharp counters, Sanchez boxed like a master in his first venture into genuine world-class. Lopez was soon marked up and bleeding from the eyes, surviving inspections by the ringside doctor in both the sixth and seventh rounds. Lopez bit down on his gumshield and tried desperately to turn the fight around; as he had in many previous contests, but the younger Mexican was an elusive target. Early in round thirteen, Sanchez stepped in with a thudding lead-right hand that staggered the tired champion. A follow-up flurry brought referee Waldemar Schmidt’s intervention at 0:51 of the round. A star was born.

After the fight when asked about his strategy, the new champion said it had been his plan to “stay off the ropes, box him and be intelligent and smart”. He had done just that and was now WBC champion of the world.

Just two months after scoring his biggest win, the new champion made his first defence against tough young veteran Rubin Castillo, winning a clear fifteen round decision. Two fights earlier, Castillo had lost to Alexis Arguello in another WBC title fight the weight division above. Interestingly, Castillo would stop both Antonio Becerra and Juan Escobar in his career; the two men who provided the only blemishes on Sanchez’ otherwise perfect record.

On June 21 1980, Sanchez faced former victim Lopez in a rematch. Before the fight, Lopez had stated that the previous loss had been a case of “beginners luck” and swore to beat Salvador this time. The rematch was a little closer but still the younger man ground the resistance out of “Little Red” for a fourteen-round stoppage.

The counter-punching Mexican ended the year with two conflicting points victories; in September he ground out a majority decision over tall Patrick Ford. Ford was unbeaten and proud, but Salvador looked laboured, even disinterested through-out the contest. However, the following December, the wiry champion was back to his best out-scoring another young veteran in Juan La Porte. The two were friends but Sanchez had too many moves for the Puerto Rican and won unanimously.

Salvador Sanchez opened 1981 with a commanding tenth-round stoppage of long-time European champion Roberto Castanon of Spain before pounding out a ten round decision over game Nicky Perez in July. This fight served as a warm up for the Mexican star’s first super fight the following month.

“Bazooka”

The 22-year-old champion’s fifth defence was to be against long-reigning WBC super-bantamweight champion Wilfredo Gomez. Puerto Rican Gomez was an outstanding 32-0-1 (32) and 14-0 (14) in world title fights. At 24 “Bazooka” was at the peak of his powers and supremely confident of knocking out Sanchez as he had every opponent he had ever faced. The build up turned ugly on several occasions as Gomez threw insults repeatedly at the placid champion. The two were not only polar opposites as fighters but also as people; Sanchez was quiet, intelligent and measured, Gomez aggressive, confrontational and fiery.

As the night of the fight drew near, Gomez was made a 2-1 favourite to continue his incredible knock-out streak. The naturally smaller man expected to stop the less-explosive featherweight king sooner or later in the fight.

The opening bell rang and the two greats locked horns in center-ring. Gomez was the first to strike; backing Sanchez onto the ropes and landing two powerful head shots. No sooner had the punches landed when Sanchez countered with a short right and a left hook to send Gomez flailing to the canvas. The shorter man rose to his feet and looked clear headed, but was met with a fusillade of leather; the Mexican went all-out to end the fight there and then. Lead rights, left hooks and upper-cuts all landed and had the Puerto Rican staggering all around the ring in desperate trouble. Gomez was very lucky to make it to the bell ending the round.

The proud Gomez fought hard to get back into the contest in the following rounds but was getting marked up, with swellings around both eyes.

Gomez gamely kept the pressure on “Chava” but by the seventh he was tiring and was struggling to see the punches of Sanchez coming as his eyes were now just slits. In the eighth, Wilfredo tore into Sanchez in a final effort to turn the tide. Both warriors landed hard shots before a huge, long right-hand landed flush on Gomez’ chin, forcing the battered Puerto Rican to sag on the ropes. The poker-faced Mexican stepped in to batter his floundering foe to bring referee Carlos Badea’s intervention and end a memorable fight.

The gifted Mexican was now no longer a mere champion but a super-star. Sanchez’ commanding win against a dangerous and skilled opponent turned heads all over the world. He was now in the upper-echelon of the world’s best fighters and looking for even more super-fights against other fellow champions.

Four months after his greatest win, Salvador defended against England’s former amateur stand-out Pat Cowdell in Texas. Cowdell was a massive underdog, expected to be beaten easily. Although only 19-2 as a pro’, Cowdell was a four time ABA champion an Olympic bronze medallist and a British champion. He trained like a demon and fought the fight of his life against the streaking champion.

Sanchez, perhaps a little under-motivated, struggled to solve plucky Cowdell’s crab-like style. The frustrated champion was being the victim of his own game, getting picked off and countered repeatedly. By the last, the chess-match seemed mighty close and in the balance. Both men circled and showed fast hands, but it was the champion who finished stronger, dropping the brave Brit with a powerful right in the closing seconds. Cowdell rose to be saved by the bell only to lose a split-decision, one judge giving him the fight by a single point the other two scoring clearly for the champion.

It was a fight that arguably saw Sanchez at his worst and Cowdell at his absolute best; that the afro-haired Mexican still won when below-par is testament to his champion’s heart.

In May 1982, the champion scored a routine-fifteen round decision over durable Jesus Garcia. It would be the first fight between two featherweights ever shown on American network HBO.

The champion’s next fight was scheduled for July against top-rated contender Mario Miranda, but at two weeks notice, Miranda pulled out with injury. A replacement was found; undefeated, but little-known Ghanaian Azumah Nelson.

Last Fight, Hardest Night

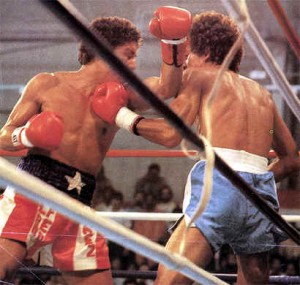

On July 21 at Madison Square Garden, Azumah Nelson stepped through the ropes to take on by far and away the best fighter he had ever faced in WBC champion Sanchez. The diminutive African turned 24-years-old just two days before the fight and was just 13-0 (10) as a pro’ compared to the Mexican’s 43-1-1 (31) record. Even though he was the older man by six months, Nelson had turned pro’ only a short time before Sanchez had started his reign as champion. No one could guess what the confident Ghanaian would go on to achieve, least of all Sanchez. A routine defence nearly turned into a nightmare for the champion, who was given one of his hardest ever fights.

Nelson, hands high, stalked the champion in the first and let his hands go. Clubbing shots caught the fleet-footed Mexican, who seemed surprised at the speed and power of his novice opponent. By round five, Nelson had forged a lead on the cards and it was clear for all to see Sanchez was struggling to keep Nelson off. What shots did land from the Mexican bounced off the head of the rampaging challenger.

Digging deep into his experience, the proud Mexican started pounding the body to try and slow the powerful challenger down. After each Sanchez combination a sharp left hook to the body, sometimes two, would sink into the African’s ribs. Slowly the champion gained a foothold.

In round seven Sanchez landed a peach of a left hook that had Nelson doing a drunken dance before a series of follow-up punches dropped the challenger for the first time. Nelson was hurt but got to his feet and made it to the bell.

Through rounds eight to ten, Sanchez continued his good work but could never relax against the dangerous African. Salvador wasn’t moving as well as he had in other fights but was starting to time his left hook to perfection.

At the end of round eleven, the champion was backed to the ropes where Nelson opened up to have the taller champion in serious trouble. Sanchez kept his poker-face but was clearly shaken and was relieved to hear the sound of the bell.

Going into the last round of this hard, hard fight, the general consensus was that the champion was a hair in front; in fact two of the judges had him narrowly ahead and the third had Nelson a point up. The challenger was completely exhausted but knew he needed to finish in a big way to stand any chance of becoming champion. He opened up in a desperate bid to flatten Sanchez, but now his blows lacked the speed of the earlier rounds and now the champion was having no trouble landing his pet punches. Nelson was shaken to his boots several times but kept doggedly trying to fight back. With blood gushing from his mouth, Nelson was finally dropped by another big left hook. The African somehow got to his feet before a last, cuffing flurry from the champion forced the ref’ to step in and stop a titanic fight at the 1:49 mark.

Unknown before the fight, “The Professor” wouldn’t lose again for eight years and would be fighting at top level for another fifteen.

On August 12 1982, Salvador Sanchez climbed into his white Porsche 928S after an evening out with friends. On the way home he attempted to over-take a truck when he collided with another truck head-on. He died instantly. He was just 23-years-old and left a widow and two young sons.

Three days later, Sanchez was buried at the Church of Santa Maria del Buen Suceso. It was the Church he had been baptised in and also had his communion. The funeral was attended by 50,000 mourners, testament to the young man’s immense popularity.

It was said after his tragic death that Salvador often spoke of dying at a young age, telling many friends and family members how he wanted his funeral to be.

Friends spoke of how Salvador had wanted to retire after his next big win to become a doctor.

Legacy

Salvador Sanchez was a great fighter who, almost definitely, would have gone on to further great victories. He had a rematch scheduled for the month after his death against Juan La Porte and was rumoured to be very close to signing fights with Alexis Arguello or a return with Wilfredo Gomez.

The Mexican was primarily a counter-puncher but could also stand and trade and was adept at fighting off the ropes. He held his hands low but would move his head and raise his gloves when in punching distance. He was very light on his feet and extremely fit due to a torrid training regime that saw him regularly spar five-minute rounds as well as running between eight and ten miles, six days a week in the mountains.

Sanchez was sometimes criticised for fighting to the level of the opponent; struggling with Patrick Ford and Pat Cowdell yet destroying Lopez and Wilfredo Gomez. Yet the great Mexican always found a way to win; a sign of a true champion.

The baby-faced fighter also received negative comments for never squaring off with fellow featherweight champion Eusebio Pedroza from Panama who was WBA champion through all of the WBC champion’s reign. Pedroza was a mover, smart and savvy but it’s questionable whether he could have destroyed the likes of Lopez, Gomez and Nelson as the Mexican did.

The Sanchez legacy lives on in his hometown of Santiago Tianguistenco, the people paying a four-day homage every August 12 to celebrate Salvador’s life and career. Sanchez’ mother and widow still live there and attend every year. Widow Theresa never remarried.

Another Salvador Sanchez turned pro’ in 2005; the legend’s nephew, who is now 24-4-3 (13). 25-year-old Salvador Sanchez II was born three years after his uncle’s death and carries with him many similarities to his famous relative. Also born and raised in Santiago Tianguistenco, Sanchez II turned pro’ after only a handful of amateur fights and even fights like his legendary uncle. He also sports the famous afro hair-style and even wears his uncle’s famous blue boxing trunks to his fights. He may not be quite as talented as the original Sanchez, but Salvador is proving a popular fighter who may one day be granted his dream of a world title shot (at featherweight, naturally).

Salvador Sanchez was posthumously inducted into the International Hall Of Fame in 1991. Sports equipment specialist and fight fan Grant Phillips has much memorabilia of the great Mexican and hopes one day to be able to open a museum in his hero’s memory. There is also reportedly a movie about the Mexican’s short life in the works also.

RIP Salvador Sanchez 1959-1982

Speak Your Mind